The Final Days of Maria Callas

Maria Callas the artist remains eternal but what of Maria the woman, who suffered in silence and died alone? ‘Focus on her art, her fans cry, as though the woman commanding the voice was, in her words, nothing more than a goddamned singing machine’.

By Lyndsy Spence

A common misconception among her fans was that Callas wanted to return to the stage and the loss of her voice resulted in her death. In the real world, women do not die because they cannot sing. In reality, she was ‘fed up with the whole business’ and her nerves could not stand the strain of performing. She was suffering from dermatomyositis, an autoimmune disease that causes muscle weakness, and to an extent, affects the central nervous system. It explains the mysterious ailments that first appeared in the early 1950s and was the reason she lost control of her voice. Professor Mario Giacovazzo diagnosed the disease in 1975, two years before Callas’s death, but she did not die of it. Other factors contributed to her demise.

Callas once said, «Only when I was singing did I feel loved», realising, correctly, that her gift made her special. A musical genius, her approach to learning the art of Bel Canto and her operatic career has not been surpassed. Everybody wanted to listen to the voice but nobody wanted to hear of her suffering. Symptoms came and went: aches and pains, chills, fatigue and insomnia, sensitivity to lights and temperature, vertigo, eczema-like rashes, low blood pressure, lipoedema, and glaucoma which saw her lose her vision. «You women are crazy», Callas was told by her Italian doctor when she sought medical advice.

So, for twenty-five years, she remained undiagnosed and in the dark, which put a strain not only on her body but her mental health. One does not have to be an expert to understand the physical demands that full-length operas placed on Callas in the 1950s and 60s.

When her voice almost cracked singing ‘Casta Diva’ in Norma before the Italian president in Rome in 1958, an audience member shouted, «Why don’t you go back to Milan, you have already cost us a million lire». The Italian audiences who once called her La Divina and pelted her with carnations now orchestrated her demise and the government tried to ban her from singing in State-run opera houses. Her voice had also cracked during Medea at La Scala in 1962, no wonder given the fluid on her vocal cords and her abdominal hernia, which, at times, caused internal bleeding.

«Only when I was singing did I feel loved»

She was fitted with polypropylene mesh, or ‘internal plastic’ as she called it, which exacerbated her pain. In 1965, during a performance of Norma in Paris, her voice gave out and she collapsed backstage and had to be revived with coramine, then given to mountaineers to increase their endurance at high altitudes. Also in 1965, she sang her final full-length opera, Tosca, at Covent Garden, in the throes of a nervous breakdown. «Only the ashes were seen, the fire was extinguished», the critics wrote. Perhaps, then, the myth of Callas was born to compensate for her vocal decline.

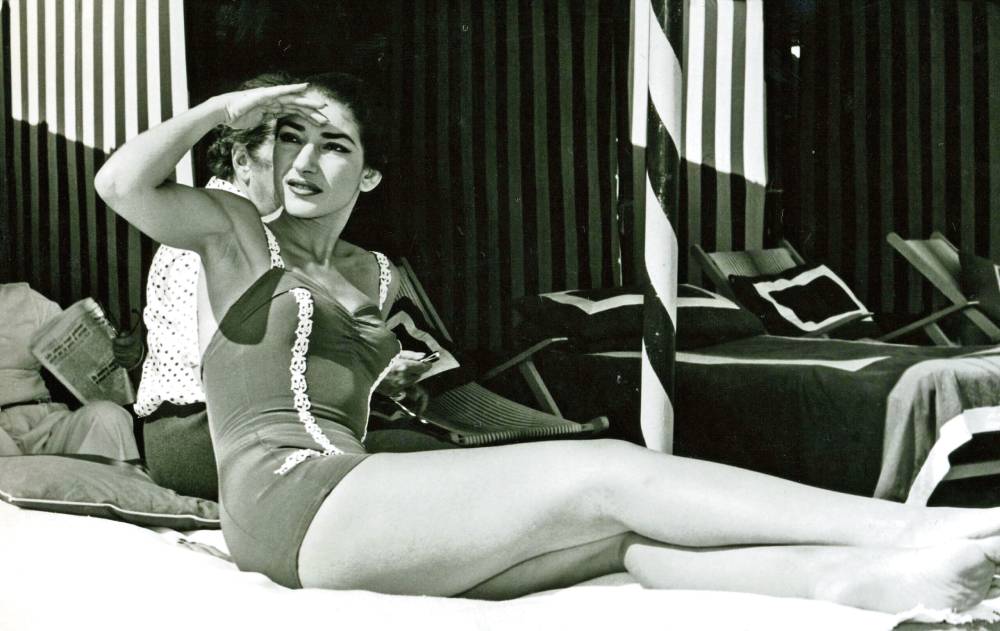

During the height of Callas’s career, it seemed like she had the world at her feet: she was beautiful, talented, and a global superstar. Nobody could have known that she was suffering from exhaustion and an eating disorder, having lost half of her body weight after a course of iodine injections in her thyroid. Her weight had been the subject of critics and audiences alike, with someone asking, «Why is she so fat?» during a performance of Aida in 1949. The criticism began in her teens, at the Athens Conservatory, where her fellow students called her «rather fat, rather slatternly and thick in the leg» and some offered to brush her hair and wash her clothes. «She just looked at us», one of the girls later recalled, «like a lost soul». Likewise, the famous designer, Biki, refused to dress her unless she lost weight and recoiled at her badly fitted suit and plastic earrings. Her colleagues at La Scala, dared her to stand on the scales and she was humiliated by the reading: she weighed almost two hundred pounds, which brought back the shame and rejection she had felt as a girl. As a result, she became regimental about food, weighing and recording everything she ate, and cutting recipes from magazines that she never made. If anything, Callas knew how to survive, a skill honed in Athens during the Axis Occupation of Greece.

She never forgot the hunger she felt during the early days of the war how she rummaged in bins for morsels of food and the desperation of walking for miles to find something to eat. The starving and dead Athenians slumped in doorways were etched into her mind. To survive, she sang for the Italians and Germans, the latter having taken over the Greek theatres. Later, she lay on her apartment floor as bullets flew past her window, during the civil war. She would find a similar strength in the combative worlds of opera and celebrity – by the late 1950s, she was the most famous diva in the world. No longer just an artist appealing to her fanbase, she became tabloid fodder and cancellations, feuds with her colleagues, namely Renata Tebaldi, and a firing from the Metropolitan Opera blotted her reputation and career. Her mental health was fragile and she told the public she was suffering from influenza, as in those days mental illness was taboo. She turned to Dr. Feelgood (Dr. Max Jacobson), who administered injections of vitamins, amphetamines, and methamphetamines, otherwise known as Speed.

The artist and woman were always in conflict: Callas could command from the stage, but at home, she was bound by the restrictions of ordinary women. Firstly before her fame, when her mother forced her to sing for enemy soldiers in exchange for food; the alternative was prostitution, which she rejected. After the war, she was repatriated to New York, where she was born, and reunited with her father but he only wanted her as a servant. She worked as a waitress and babysitter to pay for her room at the Times Square Hotel, a dingy establishment in Hell’s Kitchen. In dire straits in America, she accepted a contract to sing La Gioconda at the Verona Festival in 1947 and met Battista Meneghini, an Italian brick manufacturer twice her age, whom she called, «My master, my man, my consolation, my heart and brain, my food, my everything». They married in 1949 and when she asked him for a baby, he refused: it would jeopardise her career. Meneghini was, at that point, her manager, and her star was in ascent. A decade later, she discovered he had squandered her fortune.

Despite being famous, Callas never forgot how it felt to be unwanted. On the day of her birth, 2 December 1923, her parents, George and Litsa Kalogeropoulos (later Kalos), wanted a boy and refused to look at her. Neither could remember the exact day she was born nor could they agree on a name, eventually calling her Sophie Cecilia Maria Anna Kalos.

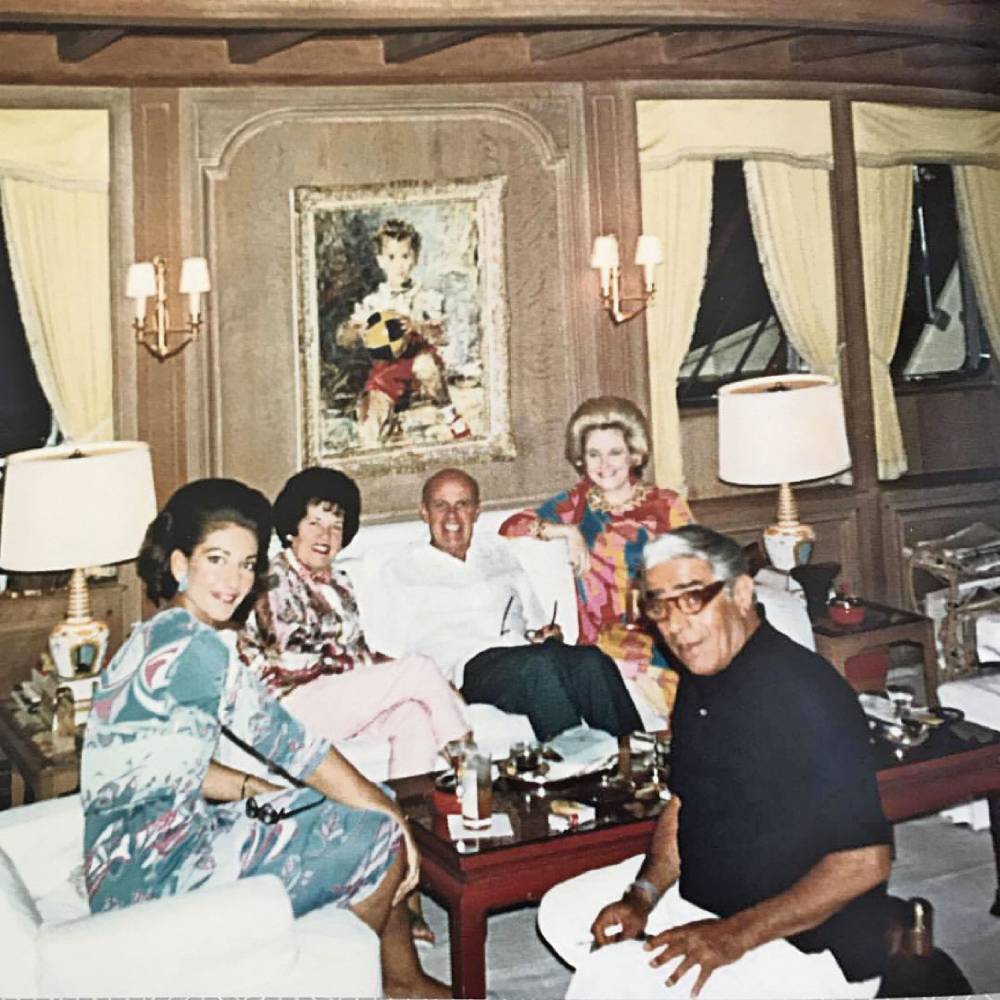

Always looking for love, she believed she had found it, in 1959, with the Greek shipping billionaire, Aristotle Onassis. However, Meneghini refused to consent to an American divorce – divorce in Italy, where they married was illegal – unless she transferred her recording royalties to him. In early 1960, Callas became pregnant with Onassis’s child, but he demanded she get an abortion – she would miscarry, as she would again in 1963.

For the next decade, Callas lived a nomadic life on Onassis’s yacht, the Christina, and followed him around the world. She hoped he would marry her but instead, he chose Jacqueline Kennedy, the former First Lady of the United States, in October 1968. In the aftermath, she starred in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film, Medea, taught masterclasses at the Juilliard School of Music, and had a brief affair with its director, Peter Mennin. In 1973-74, Callas went on a world concert tour with Giuseppe Di Stefano, her colleague from the 1950s and they began an affair which ended badly when he refused to leave his wife. Her health was declining and neurological issues affected her voice and forced her to cancel performances.

It did not help that she accidentally overdosed, more than once, on sleeping pills – Mandrax, first introduced to her by Onassis. Having been diagnosed with Dermatomyositis in 1975, she began to take steroids to alleviate her symptoms. «Now with his cure, I am much calmer», she wrote to her godfather. «Pills, of course, but good ones, not heavy drugs». However, she stopped taking them, as she gained weight and her symptoms returned, causing her to suffer throughout the day and difficulty sleeping at night. In her final days, she self-medicated with Mandrax, a dangerous drug known to sedate the nervous system, obtained from her sister in Athens and friend, Vasso Devetzi, who was later revealed to be a con woman. She did this to ease her pain and make life bearable – the myth of Callas could not sustain her. «To tell you the truth», she once said, «I do not like being called “La Divina.” I resent it. I adorn Maria Callas. And I am only a woman».

On 16 September 1977, Callas died suddenly, aged 53, in her Paris apartment.